“… so that the history of architecture would coincide with the history of ideas once more.”

– Rem Koolhaas, Berlin: A Green Archipelago, 1977

‘Revisiting Postmodernity’ is the title of a series of six seminars that have been held within the postgraduate program of the Faculty of Architecture at the TU Delft each academic year since 2014.

The seminar is based on the hypothesis that architecture can be understood as a form of cultural reflection and expression that ultimately addresses (deliberately or not) most profound assumptions and (in its most lucid moments) questions concerning human existence. As such, architecture can be considered as epistemological discipline that throughout its history has constructed, represented, and recorded the cultures within which it existed; its various registers ranging from the practicalities of life to its most thorough ideas.

Consequently, the seminar approaches architecture as an intellectual discipline that is grounded in the reflection about its own history, the history of cultural ideas, and the dialogue between these two fields. Even though Western Modernity is often characterized by its disruptive logics, an argumentation echoed by protagonists in architecture not only since modernist and postmodernist avant-garde movements, much continuity can be found in the existence of basic disciplinary notions as starting point for ever new interpretations. Such notions have established discursive lineages, collections of statements across various periods of time and geographies. Understanding them as intersections between architectural and cultural theory can establish the grounds for a contemporary reflexive and speculative practice in architecture.

The seminar is composed of four chapters: collection, type, program, reflection.

“Indeed, the world can no longer be understood… The only thing one can do is to collect the world.“

– Boris Groys, The Logic of the Collection, 1998

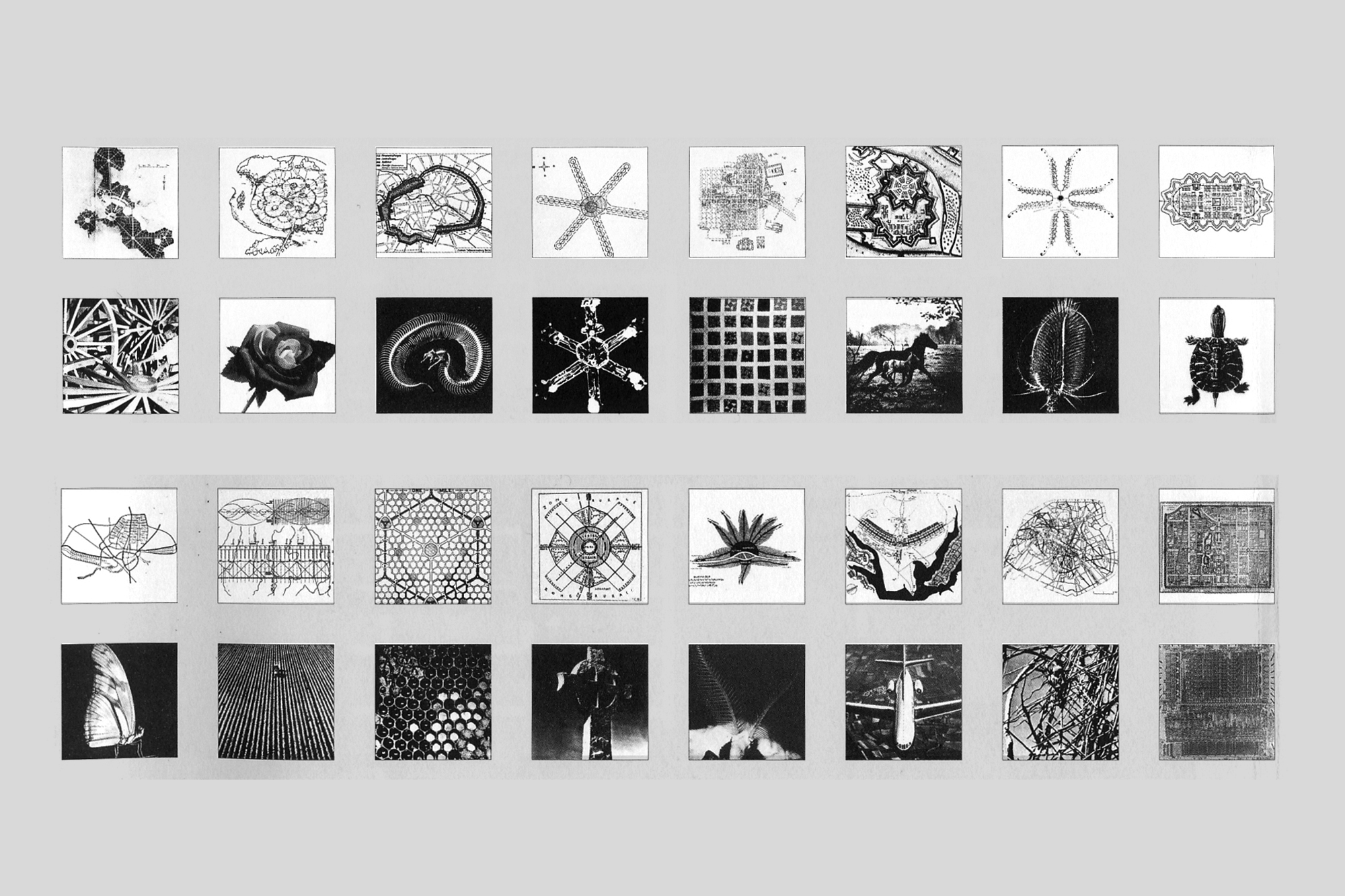

Responding to the increasing differentiation of Western modern culture, the practice of collecting its ever growing spectrum of cultural products (ideas, forms of expression, subjectivities, objects, etc.) has become one of its characteristic feature and has entered the disciplines of art and architecture alike. Systematically collecting had become an essential technique during 18th century Enlightenment inventory of the world as much as during 19th century emergence of bourgeois and industrial culture. With the advent of postwar culture in the 20th century, the notion of difference (as prerequisite for any act of collecting) has become a definitive paradigm of Western societies.

Postmodern positions in art and architecture have responded to this shift towards difference and have applied collecting as guiding logic of their thinking and practice. The idea to approach the urban field, city, and the architectural project as conceptual collections has defined innovative practices in art and architecture. The notion of collection is exemplary present in Robert Smithson’s investigations of the entropic suburban landscape, has framed Oswald Mathias Ungers’ thinking and practicing of architecture, and from here has left its imprints on the young Rem Koolhaas and the early work of OMA.

“To raise the question of typology in architecture is to raise a question of the nature of the architectural work itself.”

– Rafael Moneo, On Typology, 1978

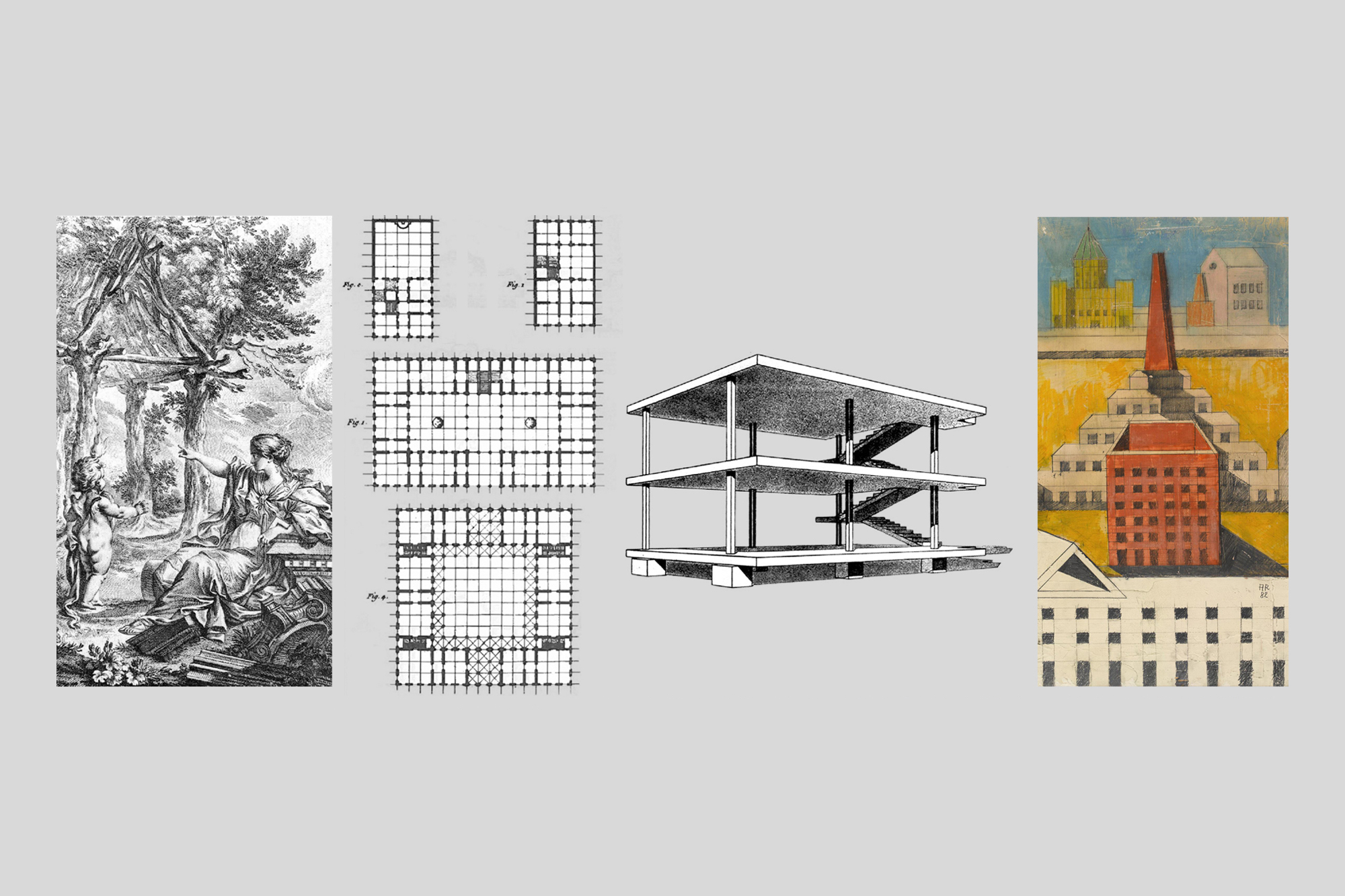

The rediscovery and critical reformulation of history has been considered as another defining feature of postmodernist thought and practice. The study of history in art and architecture has appeared with the Renaissance, has been rediscovered as resource for knowledge during the Enlightenment period, and has come to its foundational moment as modern disciplines since the mid-19th century. Postmodernity is marked by another wave of critical assessment of history in cultural and architectural theory alike. Characteristic to both fields is their productive return to and scrutiny of the beginnings of modernity.

Central to the revisiting of history in postmodernist architecture is the notion of ‘type’, a term that in some discursive positions is coupled with the idea of architecture as autonomous discipline. Type served as conceptual key vehicle in the postwar critique of ideological modernism and aimed at disconnecting and isolating the notion of ‘form’ from its modernist coupling with ‘function’. One of the most original and proliferating proposals was the anchoring of type in the conceptualization of the city by means of morphology, formulating the influential idea of an ‘architecture of the city’ (Aldo Rossi).

“Atmosphere becomes the basis of political action.”

– Mark Wigley, Constant’s New Babylon: The Hyper-Architecture of Desire, 1998

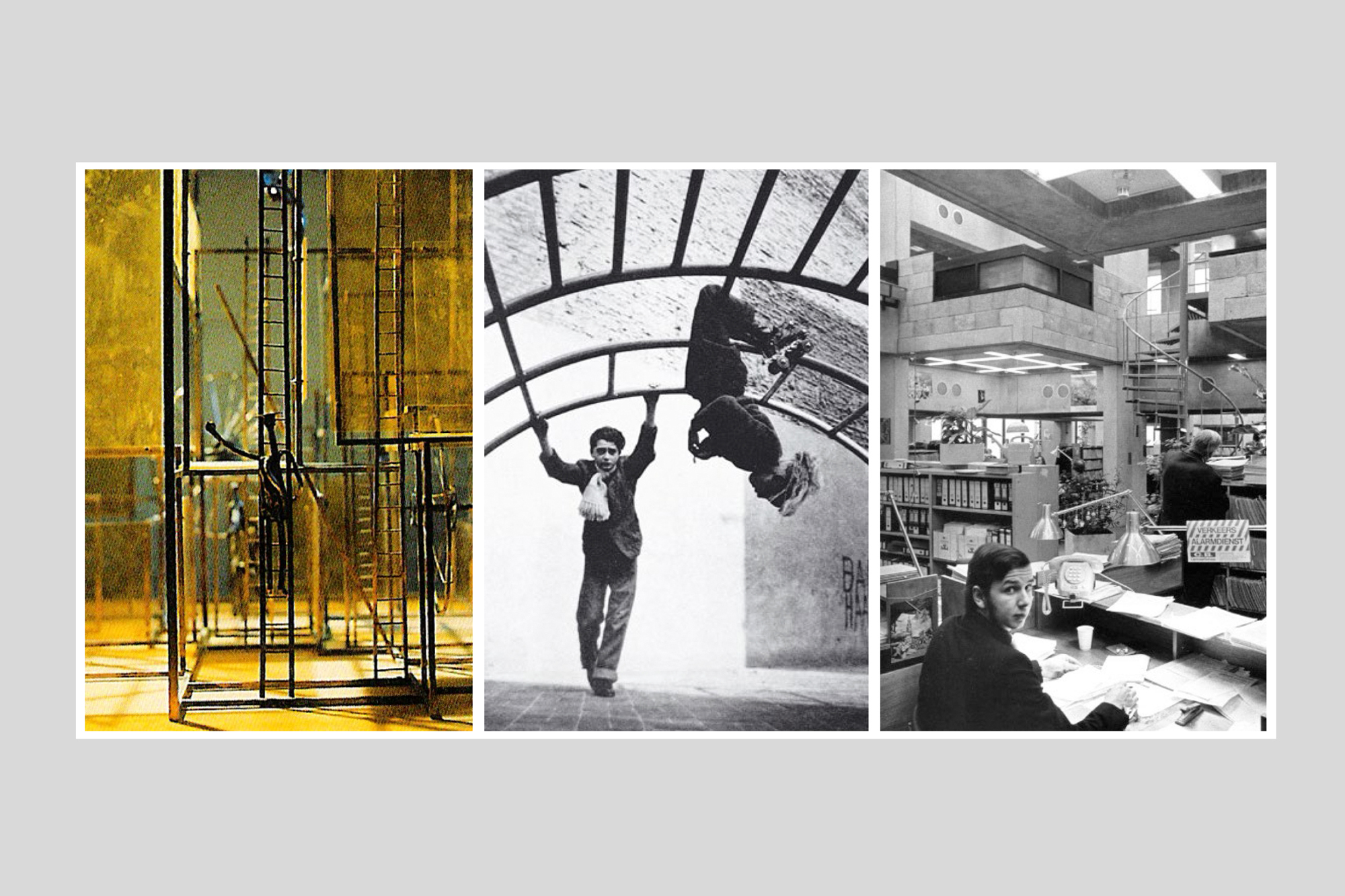

Subjectivity as a notion referring to the cultural constructing the individual and the social, as site of political production and locus of emancipation, has been at the heart of Western modern culture across its distinctive periods. Architecture has been an important ally of such constructivism. In postwar 20th century, from the debris of a failed culture, the affirmation and study of minority positions (such as, for instance, the sexual other, the ethnic other, the non-human other) has become a defining theme in everyday life and cultural theory alike.

If disconnecting form from its modernist binding to program had constituted one essential vector of critique in postmodern architecture, then the inverse action produced another, no less influential examination. The study on the ‘production of space’ and the ‘critique of everyday life’ (both terms by Henri Lefebvre) provided the impulse for the emergence of an equally productive body of postmodernist work that sought to ground the architectural project in its potential agency of co-constructing social space. The seminar investigates the intellectual milieus that both postmodernist positions have produced in Continental and Anglo-Saxon academia and practice.

“Humanism’s restricted notion of what counts as the human is one of the keys to understand how we got to a post-human turn at all.”

– Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman, 2013

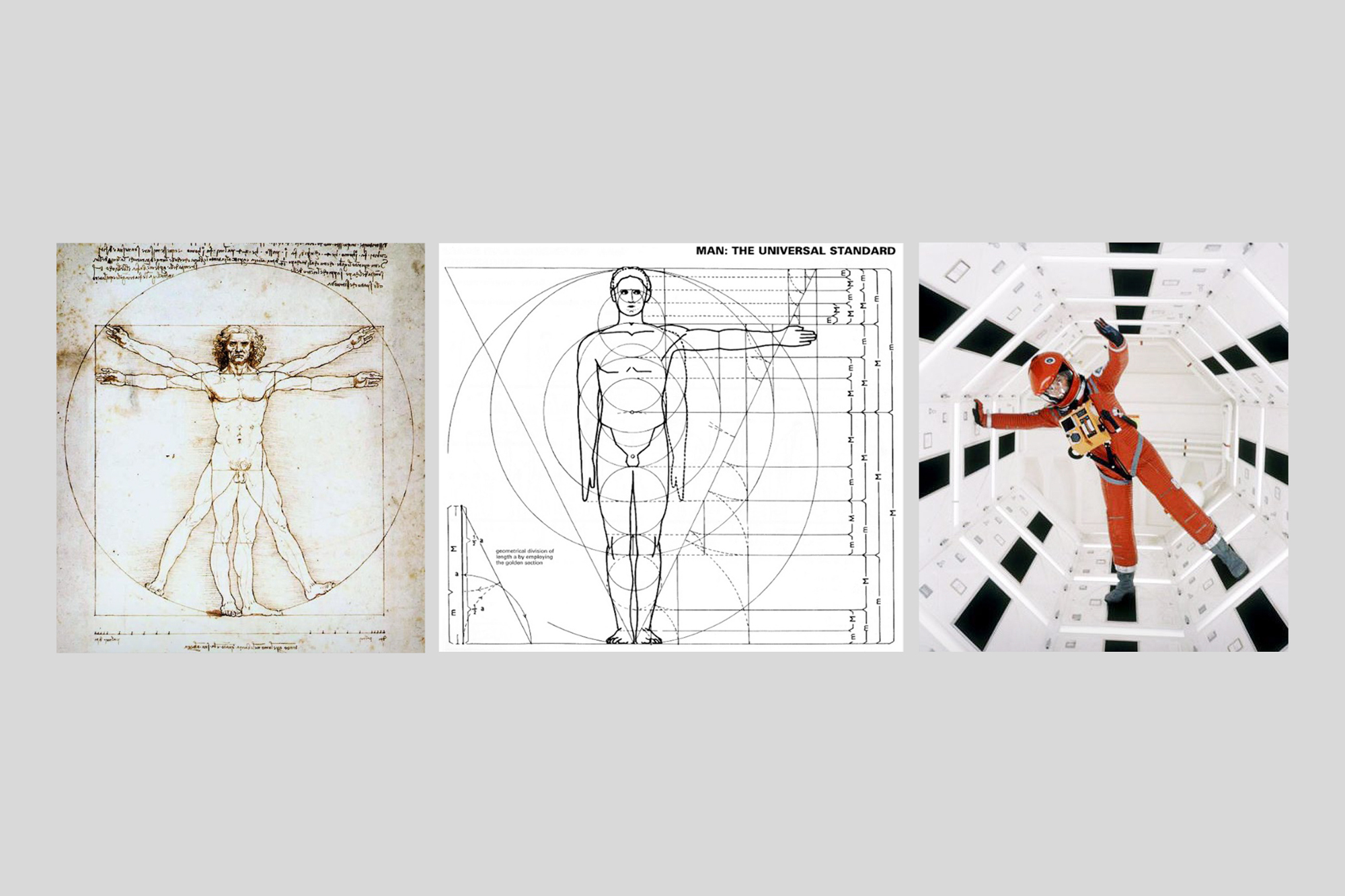

Humanism, a term invented in the early 19th century and a notion with a complex history of heterogeneous, at times even contradictory meanings and applications, has been one of the persistent, widely influential, underlying specters of Western modernity. The normative ideology that is carried within this term has been exposed to fierce critique since the beginnings of the 20th century; a critique manifest particularly also in the fields of literature, arts, and architecture. The antihumanism of the early 20th century avant-garde art movements resurfaced in the neo-avant-garde positions of architectural postmodernism, in particular those influenced by French poststructuralist critical thought. Today, posthuman cultural theory as culmination of 20th century minority movements and theories (such as feminism, post-colonialism, environmentalism) constitutes a powerful critical reflection addressing some of the most pertinent cultural challenges of Western societies.

The seminar concludes with investigating some aspects of posthuman critique as one metanarrative of contemporary cultural theory and suggesting it as intellectual vehicle to build a critical framework for an actual, emancipated, speculative position in architecture.